4 Impact of green infrastructure on property values

Many studies have found green infrastructure has positive impacts on property values:

“Transferring water resource to public ownership will increase a property’s sale price by 0.0353% for a wetland and 0.1177% for a stream” (Netusil, 2013);

“Properties on tree-lined streets are valued at up to 30% more than those on streets without trees” (“Benefits of Green Infrastructure”);

“Realtor based estimates of street tree versus non street tree comparable streets relate a $15-25,000 increase in home or business value” (Burden, 2006);

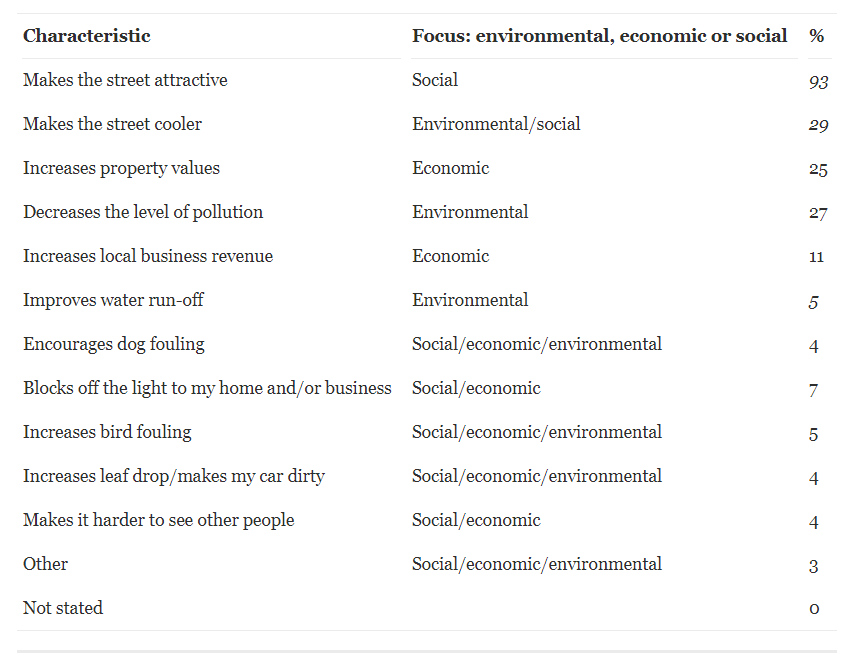

25% of survey participants see increasing property values (Mell et al., 2013);

“Marginal benefits to one household of preserving neighboring open space range from $994 to $3,307 per acre of farmland that is preserved, depending on whether it is publicly or privately owned” (Irwin, 2002);

“The effect of neighborhood association-owned forest and water feature was approximately 8% at the mean sale price with a value of $14488 for association-owned forests, and $14681 for a water feature” (Bowman et al., 2012); and

“Increase in home price is approximately $18 for every acre of public park within walking distance” (Bowman et al., 2012).

“NDSs also generate broad public appeal and may even increase the property value of retrofitted neighborhoods” (“Incorporating Water Quality Features,” 2020).

Netusil (2013) mentioned, “Using the spatial lag model coefficients…transferring 1000 square feet of a privately owned water resource to public ownership will increase a property’s sale price by 0.0353% for a wetland and 0.1177% for a stream. These values can be used to calculate a lower-bound benefit estimate for an acquisition by creating a ¼ mile buffer around single-family residential properties and determining, for a specific site, how many of those buffers overlap the water resource.”

“Street trees and green infrastructure enhance aesthetic qualities and provide a significant neighborhood amenity. Properties on tree-lined streets are valued at up to 30% more than those on streets without trees” (“Benefits of Green Infrastructure”).

“Realtor based estimates of street tree versus non street tree comparable streets relate a $15-25,000 increase in home or business value. This often adds to the base tax base and operations budgets of a city allowing for added street maintenance. Future economic analysis may determine that this is a break-even for city maintenance budgets” (Burden, 2006).

Below is how people see the impact of green infrastructure on property value increase for investment.

Source: Mell et al., 2013

“Tyra¨vinen and Miettinen (2000) conduct a careful study of the spillover effects of the various attributes associated with urban forests on housing prices in a semi-rural area in Finland. They find that the distance to the nearest small area of forest has a negative and significant effect, and that the presence of a forest view from the housing unit has a positive influence…Given the conditions within the Maryland study area, which are characterized by relatively high rates of population growth and land conversion, we find that the marginal benefits to one household of preserving neighboring open space range from $994 to $3,307 per acre of farmland that is preserved, depending on whether it is publicly or privately owned” (Irwin, 2002).

“Consequently the neighborhoods in which they are built will see an increase in property values and habitability due both the functional and aesthetic value of the bioswales” (O’Neill, 2013).

Anderson (2018) mentioned, “Additional benefits of bioswales include growth of vegetation, which has been shown to improve asphalt longevity (McPherson, 2005), mitigate the urban heat island effect, and improve local property values (Bowman, 2010).”

Bowman et al. (2012) shows many examples for valuation of conservation design and low-impact development in residential area as below.

“Public parks and nearby open space have been shown to positively influence housing prices by both proximity and amount of use (Bolitzer and Netusil, 2000, Bowman et al., 2009; Kitchen and Hendon, 1967; Lutzenhiser and Netusil, 2001).”

“The effects of neighborhood association-owned forest and water features were positive and significant. The marginal effect of these features was approximately 8% at the mean sale price with a value of $14488 for association-owned forests, and $14681 for a water feature. These findings are similar to other studies (e.g., Lorenzo et al., 2000, Ready and Abdalla, 2005) with the presence of private forests associated with higher home prices.”

“However, for publically-held open space size did matter -open space within walking distance (500 m) of a house had a marginal effect (at p < 0.057) of 0.02% per acre, which at the mean price of a home in Ames is an increase in home price of approximately $18 for every acre of public park within walking distance. As Peiser and Schwann (1993) found, this effect is miniscule when compared with the marginal effect of a similar amount of additional lot space ($24659 at the mean sale price)…previous hedonic price model studies identify the value of public open space and the significant positive effect they have on home prices within a community (Bolitzer and Netusil, 2000, Correll et al., 1978).”

“Finally, a spatial hedonic price model using 2093 homes in Ames, IA was used to estimate the effect of public and private open space on housing values. The model indicated that presence of neighborhood association-owned forest and water features as well as proximity to public parks had significant positive effects on housing prices. However, proximity to a public lake had a negative effect on home values.”

4.1 Bioswales

Specially bioswales are also known to improve local property values (Anderson, J., 2018). O’Neill (2013) mentioned that “the neighborhoods will see an increase in property values and habitability due both the functional and aesthetic value of the bioswales.” Furthermore, Ward et al., (2008) argued that the property value of the green grid in north Seattle (on street bioswales) increases about 3.5 to 5 percent.

“A preliminary analysis of the effect of LID on property values in Seattle indicates that the introduction of LIDs increased property values by 3.5 – 5 percent. Compared to similar houses (e.g., in terms of square feet of living space, building quality, lot size, etc.) in the same zip-code, houses in Seattle’s Street Edge Alternative (SEA), Broadview Green Grid, Pinehurst Green Grid, and High Point projects sold for 3.5 – 5 percent more during the period after the adjacent streets were converted to LID. This increase in value appears to be the result of the LID. Prior to the introduction of LID, the houses affected by these projects did not command a premium over their neighbors. These results suggest people are willing to pay for the combination of neighborhood amenities and environmental services provided by LID stormwater controls” (Ward et al., 2008).

“Reduced runoff stormwater volume and peak flows during inundation events, and mitigated spot flooding within the project area. Residents in the area have expressed appreciation for the aesthetic qualities of streets with natural drainage systems. The streets are favored places for neighborhood residents to take walks and are viewed as open space. Water quality has been enhanced by a lower volume of stormwater leaving the site, and by biofiltration for excess stormwater that drains from the project area” (“Pinehurst Green Grid, Seattle,” 2017).

4.2 Wastewater treatment

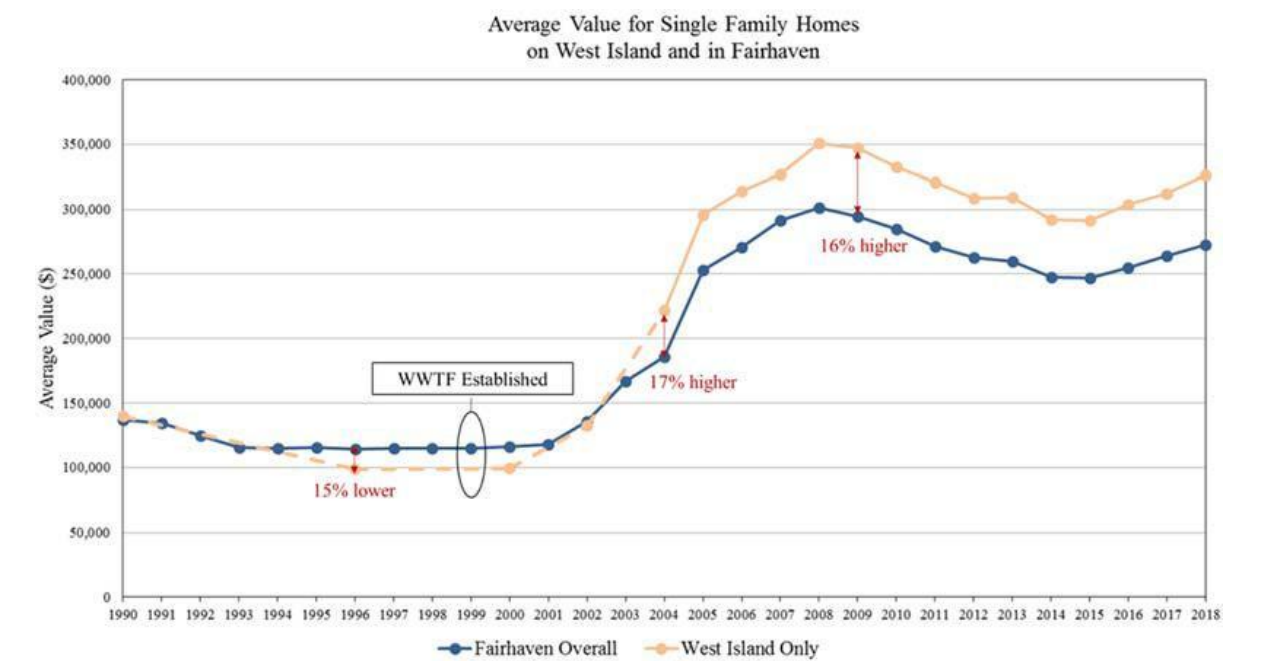

In addition, Gurdon and Jakuba (2018) shows two cases which prove increase of property values around wastewater treatment facilities.

“Between the early and mid-1990’s, the average value for a single family home on West Island was less, by approximately 15%, than the average value for a single family home in Fairhaven as a whole. The wastewater treatment facility was established in 1999, and soon after the average value for a single family home on West Island rose to become higher, by approximately 17%, than that in the rest of Fairhaven. This change remains, even after the financial crisis, with the average home value on West Island still approximately 16% higher than the rest of the Town. While home values depend on many factors, it is likely that the development of the wastewater treatment facility contributed to the increase in value for single family homes on West Island” (Gurdon and Jakuba, 2018).

Housing value trends (Source: Gurdon and Jakuba, 2018)

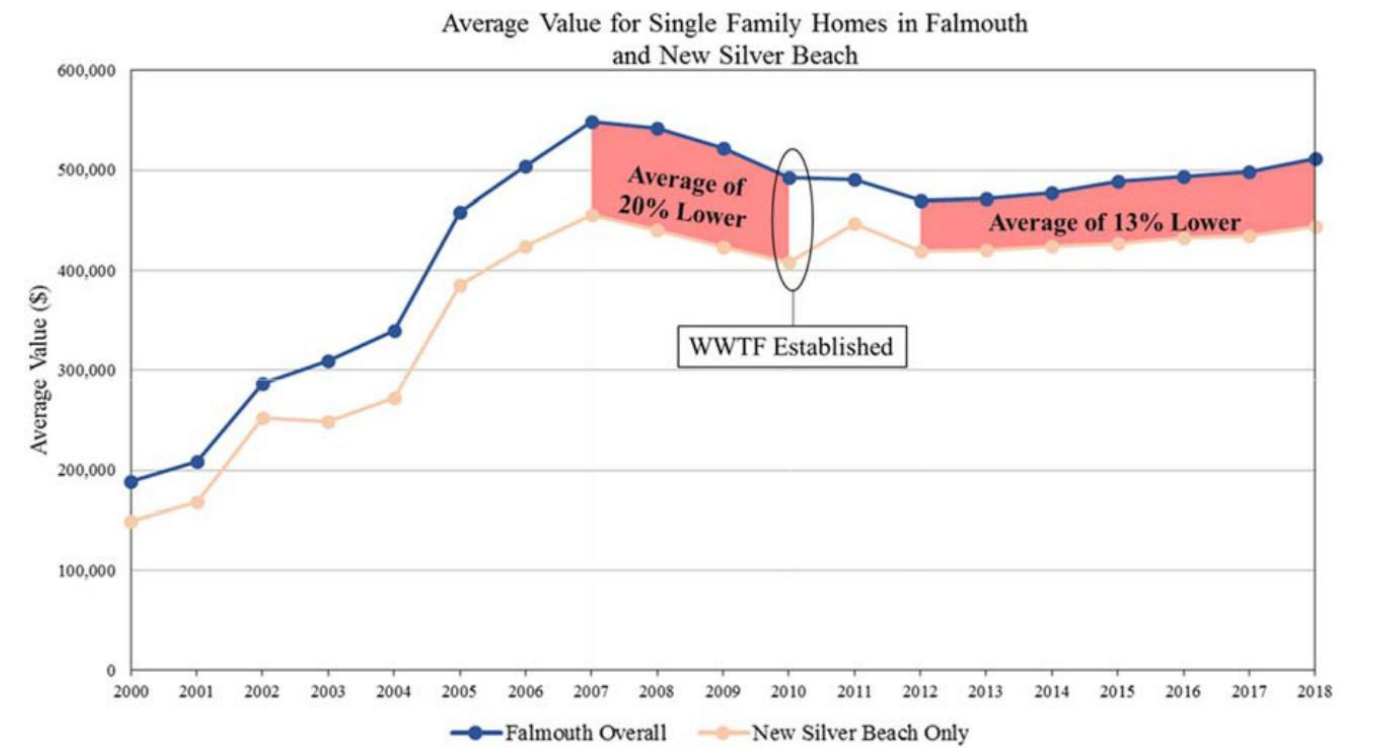

“Because the majority of these homes are used only during summer months, most are not winterized so their value tends to be lower than that of homes in the rest of Falmouth. Between 2007 and 2010, the average value for a single family home in the New Silver Beach area was 20% lower than a single family home in Falmouth. Since the wastewater treatment facility began serving homes in the New Silver Beach area in 2010, the disparity in price between single family homes in New Silver Beach and single family homes in Falmouth has narrowed. Between 2012 and 2018, the average value for a single family home in the New Silver Beach area is only 13% lower than the average value for a single family home in Falmouth” (Gurdon and Jakuba, 2018).

Housing value trend (Source: Gurdon and Jakuba, 2018)

4.3 Negative impacts on property values

On the other hand, Netusil et al. (2014) found there is a negative impact on a property’s sale price as distance from the nearest green infrastructure increases while bioswales are not significant. Netusil et al. (2014) mentioned, “Portland, Oregon has a long history of developing low-impact development facilities through its ‘green streets’ program and continues to promote these facilities as improving air and water quality, enhancing pedestrian and bicycle access and safety, expanding the amount of urban green space and wildlife habitat, and increasing property values (Environmental Services City of Portland, 2008). Findings from the present study provide support for some of these claims but challenge others. For example, we find a small but statistically significant increase in a property’s sale price as distance from the nearest facility increases. Facility type (sidewalk bioswale, corner curb extension, curb extension, or grassy bioswale) is not found to have a statistically significant effect on a property’s sale price, but a facility’s size, age, design complexity, tree canopy coverage, and abundance of facilities at the census tract or census block level do have a statistically significant effect.”